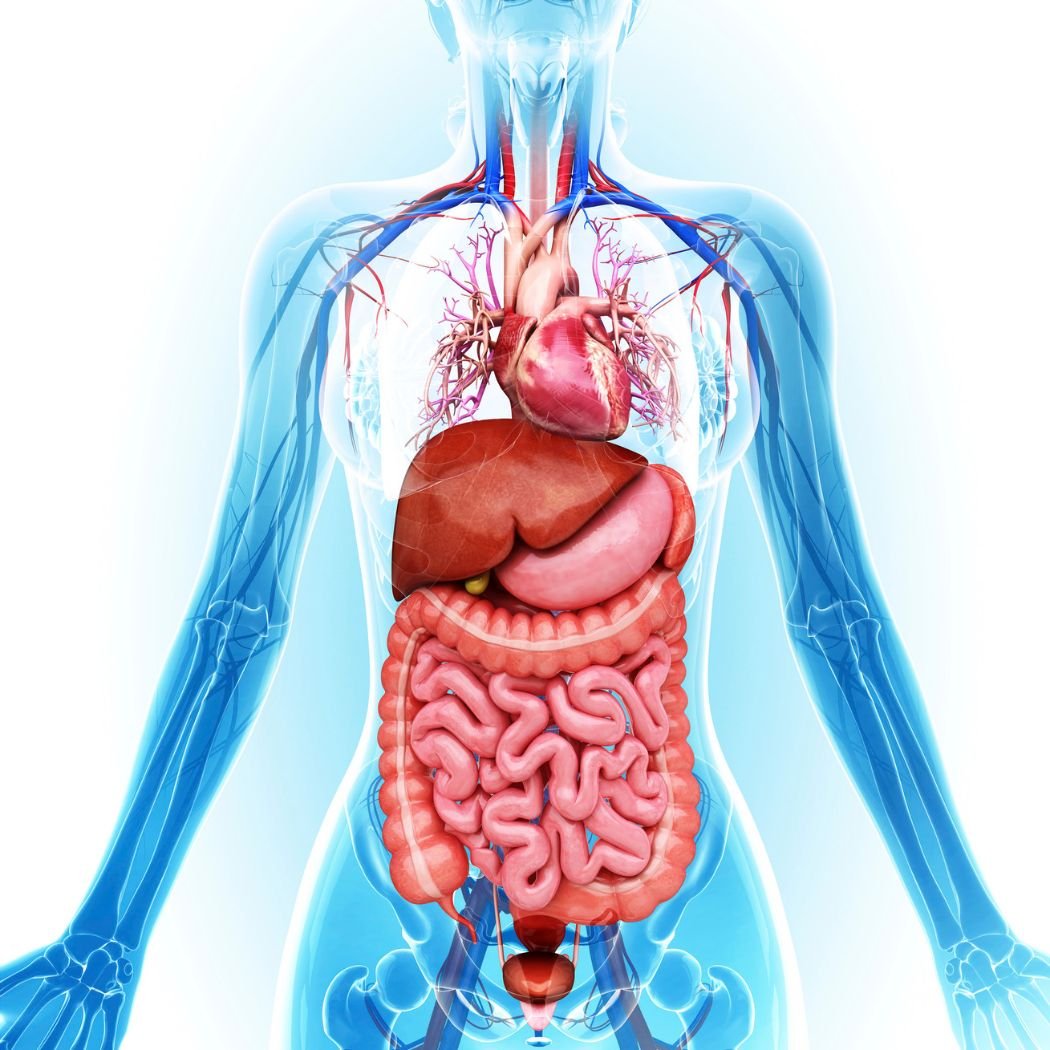

Digestive system is a complex network of organs that work together to break down food, absorb nutrients, and eliminate waste from the body. Here’s a detailed overview of its structure, function, and key components:

Structure and Function OF Digestive System

The primary function of the digestive system is to convert food into energy and basic nutrients to feed the entire body. This process involves the mechanical and chemical breakdown of food, nutrient absorption, and waste elimination.

Key Components of the Digestive System

Mouth

- Function: Digestion begins in the mouth, where mechanical digestion (chewing) breaks down food into smaller pieces, and chemical digestion starts with saliva breaking down complex carbohydrates.

- Structures: Teeth, tongue, salivary glands.

Esophagus

- Function: Acts as a conduit for food and liquids that have been swallowed into the mouth to reach the stomach.

- Structure: A muscular tube that connects the throat (pharynx) with the stomach.

Stomach

- Function: Continues the process of mechanical digestion; the stomach’s gastric acid and digestive enzymes break down food into a liquid or paste-like substance known as chyme.

- Structure: A hollow organ on the left side of the upper abdomen.

Small Intestine

- Function: Absorption of nutrients and minerals from food. The majority of digestion occurs here with the help of enzymes produced by the pancreas and bile from the liver.

- Structure: Consists of three segments – the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum.

Large Intestine (Colon)

- Function: Absorbs water and salts from the material that has not been digested as food, and is thus passed from the small intestine. It also stores waste material until it is excreted through the anus.

- Structure: Encircles the small intestine and consists of the ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon, and sigmoid colon.

Rectum and Anus

- Function: Final section of the digestive tract, where feces are stored until they leave the body through the anus.

- Structure: The rectum connects the colon to the anus.

Accessory Organs

Pancreas

The pancreas is a vital organ in the digestive and endocrine systems, playing key roles in both digestion and metabolism. Here’s an in-depth look at the structure and function of the pancreas:

Function of the Pancreas

Exocrine Function:

- Digestive Enzymes: The pancreas produces a variety of enzymes that are crucial for the digestion of nutrients in food. These enzymes include amylase for the breakdown of carbohydrates, lipase for fats, and proteases such as trypsin and chymotrypsin for proteins. These enzymes are secreted into the small intestine through the pancreatic duct.

- Bicarbonate Production: Along with digestive enzymes, the pancreas secretes bicarbonate to neutralize stomach acid entering the duodenum, the first segment of the small intestine. This neutralization is important to provide an optimal environment for pancreatic enzymes to function effectively.

Endocrine Function:

- Hormone Production: The pancreas also has an endocrine role through its secretion of important hormones that regulate blood sugar levels. The key hormones include:

- Insulin: Produced by beta cells in the pancreatic islets, insulin helps lower blood glucose levels by enabling cells to absorb glucose from the bloodstream.

- Glucagon: Produced by alpha cells, glucagon works to raise blood glucose levels by signaling the liver to release stored glucose.

- Regulation of Metabolism: Together, insulin and glucagon maintain homeostasis of blood glucose levels, which is vital for proper metabolic functioning.

Structure of the Pancreas

Location and Appearance:

- Position: The pancreas is located in the abdomen, tucked behind the stomach, close to the duodenum. It sits across the back of the abdomen, behind the stomach.

- Shape and Size: It is typically about 6 inches (about 15 cm) long and has a flat, elongated shape that is often described as looking somewhat like a fish.

Internal Structure:

- Pancreatic Ducts: The pancreas has a main duct that runs the length of the pancreas from the tail to the head, where it meets the common bile duct to form the ampulla of Vater at the duodenum. This ductal system is essential for transporting digestive enzymes out of the pancreas.

- Pancreatic Islets (Islets of Langerhans): Scattered throughout the pancreas, these are the sites of hormone production. The islets contain several types of cells, including alpha and beta cells, which produce glucagon and insulin, respectively.

Blood Supply and Nerves:

- Vascular Supply: The pancreas has a rich blood supply that is crucial for bringing nutrients to its cells and for carrying away hormones and enzymes to the rest of the body. It receives blood from branches of both the superior mesenteric artery and the splenic artery.

- Innervation: The pancreas is innervated by both the parasympathetic and sympathetic divisions of the autonomic nervous system, which regulate both exocrine and endocrine functions.

Clinical Significance

- Diseases and Disorders:

- Pancreatitis: Inflammation of the pancreas, often painful and potentially dangerous, can occur in acute or chronic forms.

- Diabetes Mellitus: A disorder involving insulin production (Type 1 Diabetes) or function (Type 2 Diabetes), significantly impacting the pancreas’ endocrine function.

- Pancreatic Cancer: Known for being particularly aggressive and having poor prognosis.

The pancreas is essential for both digestive processes and blood glucose regulation. Its dual functions make it critical to nutrition, metabolism, and overall health. Understanding the pancreas’s role and maintaining its health are crucial for preventing and managing various metabolic and digestive disorders.

Liver

Detailed Overview of the Liver

The liver is one of the most vital organs in the human body with a wide array of functions that are crucial for maintaining good health. It plays a central role in all metabolic processes in the body and is known for its ability to regenerate itself. Here’s a deeper look into the structure and functions of the liver:

Function of the Liver

Metabolism of Nutrients:

- Carbohydrates: The liver helps to maintain normal blood sugar levels by converting excess glucose into glycogen for storage. When blood glucose is low, it converts glycogen back into glucose.

- Proteins: It synthesizes various proteins important for blood clotting and other functions. It also converts ammonia, a toxic byproduct of protein metabolism, into urea, which is then excreted in the urine.

- Fats: The liver produces bile, which emulsifies fats in the digestive tract, aiding in their absorption. It also synthesizes cholesterol and certain important proteins that transport fats through the body.

Detoxification:

- Chemicals and Drugs: The liver detoxifies various metabolites, neutralizes drugs, and is involved in purifying the blood. It metabolizes drugs and other substances in a process that makes them easier for the body to excrete.

- Alcohol: The liver processes alcohol and other toxins, breaking them down and removing them from the blood.

Bile Production:

- Digestion Aid: Bile, which contains bile acids, is vital for the digestion and absorption of dietary fats and fat-soluble vitamins in the small intestine. The liver continuously secretes bile, some of which is diverted to the gallbladder for storage or directly sent to the duodenum.

Structure of the Liver

Location and Size:

- Position: The liver is located in the upper right quadrant of the abdomen, just below the diaphragm, and on top of the stomach, right kidney, and intestines.

- Size and Shape: It is the largest glandular organ in the body, weighing about 1.44–1.66 kg (3.17–3.66 lb) in adults. It has two main lobes (right and left), each made up of thousands of lobules. These lobules are the functional units of the liver.

Blood Supply:

- Dual Blood Supply: The liver has a unique blood supply. About 75% of its blood comes from the portal vein carrying nutrient-rich blood from the intestines, while the remaining 25% comes from the hepatic artery supplying oxygen-rich blood.

Histology:

- Hepatocytes: The bulk of the liver consists of hepatocytes, which are responsible for most of the metabolic, synthetic, and detoxifying functions.

- Bile Ducts: Bile produced by hepatocytes is collected by a system of ducts that flow from the lobules to the common hepatic duct.

Clinical Significance

- Liver Diseases:

- Hepatitis: Inflammation of the liver, usually caused by viruses, toxins, or autoimmunity.

- Cirrhosis: Long-term damage to the liver, often due to alcohol abuse or hepatitis, leading to scarring and liver failure.

- Liver Cancer: Several types of cancer can form in the liver, including hepatocellular carcinoma and bile duct cancer.

- Regenerative Capacity:

- Regeneration: The liver is known for its remarkable ability to regenerate itself after injury. Even after surgical removal of a portion of the liver, the remaining tissue can grow back to full size, though not always to its full original shape.

The liver’s role in digestion, metabolism, and detoxification makes it essential to many aspects of health and well-being. Its ability to repair itself is nearly unique among human organs, underscoring its importance. Maintaining liver health is crucial, given its critical functions and the rising incidence of liver diseases associated with lifestyle factors.

Gallbladder

The gallbladder is a small but vital organ involved in the digestive process, especially in the digestion of fats. Here’s an in-depth look at its structure, function, and significance in the digestive system.

Function of the Gallbladder

- Bile Storage and Concentration: The primary function of the gallbladder is to store and concentrate bile, a yellow-brown digestive enzyme produced by the liver. Bile aids in the digestion of fats by emulsifying fats in the small intestine, which increases the surface area for the action of digestive enzymes.

- Controlled Release of Bile: When fatty food enters the small intestine, it stimulates the secretion of a hormone called cholecystokinin (CCK). CCK signals the gallbladder to contract and release stored bile into the small intestine through the bile ducts. This timely release ensures that fats are broken down efficiently as they pass through the digestive tract.

Structure of the Gallbladder

- Location and Shape: The gallbladder is a small, pear-shaped organ located just beneath the liver on the right side of the abdomen. It connects to the liver and the small intestine via the biliary tract.

- Size: Typically, the gallbladder is about 8 cm in length and 4 cm in diameter when fully distended. However, its size can vary significantly depending on bile levels.

- Internal Structure: The gallbladder wall has three primary layers:

- Mucosa (Inner Layer): Lined with epithelial cells that absorb water and electrolytes from bile, making it more concentrated.

- Muscularis (Middle Layer): Contains smooth muscle fibers that contract in response to CCK, pushing the bile out into the bile duct.

- Serosa (Outer Layer): A thin layer of connective tissue that covers and protects the gallbladder.

Importance of the Gallbladder in Digestion

- Fat Digestion: By concentrating and releasing bile, the gallbladder plays a critical role in the digestion and absorption of dietary fats. Bile breaks down large fat globules into smaller droplets that enzymes can more easily digest.

- Nutrient Absorption: The emulsification of fats by bile acids facilitates the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) and essential fatty acids, which are crucial for various body functions, including vision, immune response, and blood clotting.

Gallbladder Health Concerns

- Gallstones: One of the most common gallbladder issues is the formation of gallstones, which are hard deposits that can form inside the gallbladder. Gallstones can block the flow of bile, causing pain, inflammation, and infections.

- Cholecystitis: Inflammation of the gallbladder, often due to gallstones blocking the bile ducts, leading to pain and possible serious infections.

- Cholecystectomy: Sometimes, severe or recurrent problems with gallstones or the gallbladder itself lead to the removal of the gallbladder (cholecystectomy). Fortunately, people can live without a gallbladder; bile just flows directly from the liver to the small intestine, although fat digestion may not be as efficient.

Importance of the Digestive System

The digestive system is critical to our overall health and well-being, performing essential functions that sustain life by converting food into energy, supporting immune functions, and efficiently disposing of waste. Here’s a closer examination of why the digestive system is so crucial:

Nutrient Utilization

Digestion and Absorption:

- Mechanical and Chemical Processes: The digestive system breaks down food through mechanical processes like chewing and the churning action of the stomach, as well as chemical processes involving enzymes and other digestive secretions. These processes transform complex foods into absorbable particles.

- Nutrient Absorption: The small intestine is the main site for nutrient absorption. Its highly efficient structure, lined with villi and microvilli, maximizes the surface area for absorbing nutrients into the bloodstream. This absorption is crucial for providing the body with the energy and materials needed for growth, repair, and maintenance.

Energy Production:

- Carbohydrates, Proteins, and Fats: The digestive system is responsible for extracting macronutrients—carbohydrates, proteins, and fats—from food. These macronutrients are essential for energy production, building and repairing tissues, and regulating body functions.

Immune Function

Gut Microbiome:

- Protection Against Pathogens: The gut microbiome, which consists of trillions of bacteria and other microorganisms, plays a crucial role in defending against pathogenic bacteria. The beneficial microbes compete with pathogens for nutrients and attachment sites, reducing the risk of infections.

- Synthesis of Vitamins: Some gut bacteria are vital for synthesizing essential vitamins like vitamin K and some B vitamins, which are crucial for blood clotting, energy production, and other metabolic processes.

Barrier and Immune Modulation:

- Intestinal Barrier: The intestinal lining acts as a barrier to prevent pathogens and toxins from entering the bloodstream.

- Immune Response Regulation: The cells in the gut lining also play a role in the immune system by detecting harmful pathogens and alerting the body’s immune cells.

Waste Elimination

Detoxification:

- Liver Function: The liver plays a significant role in detoxifying blood by removing toxins and other harmful substances processed during digestion. These substances are either expelled through the bile into the small intestine or filtered out by the kidneys into the urine.

- Colon Function: The colon (large intestine) is where the body reabsorbs water and mineral salts from the remaining undigested food matter and processes it into stool. Regular bowel movements help eliminate these wastes, keeping the body clean from the inside.

Excretion of Metabolic Byproducts:

- Removal of Indigestible Substances: Some components of food cannot be digested or absorbed (like dietary fiber) and are essential for maintaining healthy bowel movements and preventing constipation.

Conclusion

The digestive system is integral not only for providing the body with the nutrients it needs to function but also for maintaining immune health and eliminating waste. Each component of the digestive system—from the mouth to the colon—plays a specific role that contributes to these overarching functions. Ensuring the health of the digestive system through proper nutrition, adequate hydration, and regular physical activity is essential for overall wellness and disease prevention.